Joshua Benjamins is a PhD candidate in the Department of Ancient Greek and Roman Studies. Before coming to Berkeley, he earned a BA in Latin and History at Hillsdale College and an MA in Early Christian Studies at the University of Notre Dame. He specializes in the intellectual and cultural history of the later Roman Empire, with a special focus on Augustine and late antique Christianity.

BCSR: Please tell us a little about yourself.

Benjamins: I grew up in Ontario, Canada, the oldest of seven children. I was fortunate to receive a classical, Great Books style education in high school that spurred my interests in literature, history, philosophy, and theology. When I went to Hillsdale College for my undergraduate degree, I decided to pursue the study of Latin and Greek so as to be able to access the works that inspired me in their original languages. That’s how I came to the discipline of classics. One thing that especially attracted me about this field was that, because its boundaries are defined by time and place more than by methodologies or modes of inquiry, classics has a unique flexibility and capaciousness to it, and branches out naturally to other disciplines.

After finishing my BA, I earned an MA in the Early Christian Studies Program at the University of Notre Dame. This interdisciplinary program enabled me to pursue my interests in both classics and religious studies, with a focus on late antiquity and especially on late ancient Christianity. That set of interests brought me to Berkeley for my PhD in classics.

BCSR: Please tell us about your dissertation topic.

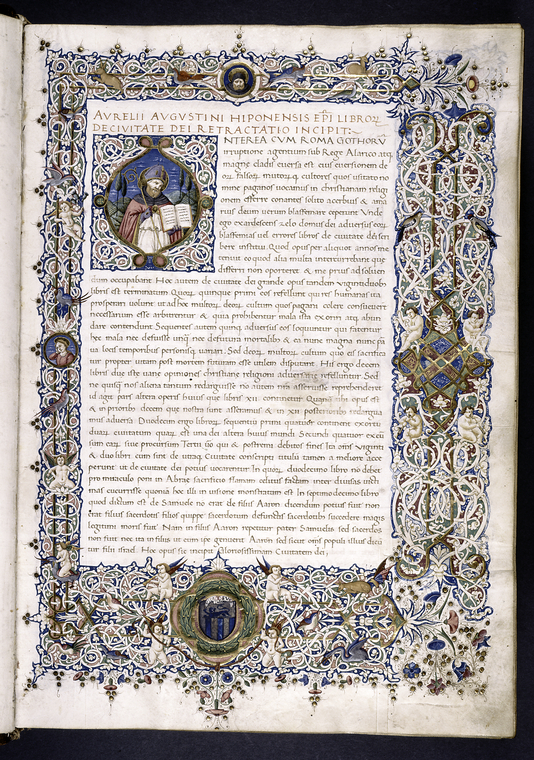

Benjamins: My dissertation is entitled “Augustine’s Rome: Reframing Time, Empire, and Masculinity after 410 AD.” In it I examine the early books of The City of God, the magnum opus of Augustine, bishop of Hippo in North Africa, together with a set of sermons in which Augustine responded to the sack of Rome by Alaric’s Goths in 410 AD. I argue that in his sermons of 410-412 and, later, in City of God, Augustine is not (as often claimed) desacralizing Rome and diminishing its historical significance, but rather is offering a revisionist account of Roman eternity, imperial ideology, and masculinity in the wake of both the Gothic sack and broader crises of the Roman empire (military, political, and religious) in the late fourth century.

A central premise of my dissertation is that Augustine’s works from the 410s not only engage with earlier exponents, historians, and critics of the Roman imperial project (from Vergil to Tacitus) but also respond to elite figures who were writing at and/or about Rome in the 380s and 390s—particularly Ammianus Marcellinus, the last great historian of the Roman empire; Symmachus, spokesman of the pagan aristocracy at Rome; Ambrose, bishop of Milan; Prudentius, a Spanish Christian poet; and Claudian, a Latin poet at the court of the emperor Honorius. These contemporaries of Augustine were engaged in a larger debate about what we might call the temporality of Rome (variously cast in terms of eternity, senescence, and rejuvenation), the masculinity of empire, and the connection between emendatio or “correction” and historical progress. I argue that Augustine is intervening in this set of elite contestations and that his City of God is a thoroughly imperial project, fashioning a new Roman identity based upon a new model of Roman manliness.

In my dissertation, I trace the contours of Augustine’s intervention along several interrelated tracks. First, Augustine’s sermons on the sack of Rome construct a novel aesthetic of Roman masculinity organized around the idea of “endurance.” By using the biblical Job as a figure for the tormented “body” of Rome and as a paragon of virtue (or manliness: virtus in Latin) manifested through suffering, Augustine ascribes moral beauty to the conjunction of a disfigured and tormented body with a suitably chastened soul. Next, Augustine critiques the ideology of an eternal Roman empire in a way that revamps both Christian and pagan versions of that ideology. Finally, Augustine offers a revisionist account of Roman virtue. Although he criticizes the morality of ancient Rome against the yardstick of Christian virtue, I show that Augustine does not altogether eschew the connection between virtue and temporal success, or felicity, which was a hallmark of Roman imperial ideology: instead, he insists that Rome’s worldwide and long-lasting empire was a due reward for the Romans’ virtue. Moreover, far from dismissing Roman history as insignificant, Augustine recuperates its didactic and exemplary value for Christian ends, particularly in his figural interpretation of Romulus’ asylum and his extended comparison of Roman Republican heroes with the Christian martyrs.

BCSR: How did you come to this topic?

Benjamins: My interest in Augustine and his philosophy of history began with a course I took in my senior year of college, entitled “The History and Philosophy of History”—a sort of capstone course to the history major. That class was a selective survey of some of the architectonic philosophies of history that have shaped the way history has been written in Western culture, especially with regard to the question of eschatology (where history is going, how it ends—what its telos is) and the legibility of the historical process. One of the readings for that course came from a little book by Robert Markus entitled Saeculum, which develops a fascinating argument about Augustine’s evolving understanding of the relationship between sacred and secular history and between history and prophecy. Markus argues that after the sack of Rome Augustine lost some of his earlier optimism about Christianized Rome being the fulfillment of biblical prophecies about the coming of God’s kingdom on earth, and that he came to a radically skeptical position about the intelligibility of divine providence in history. The book dealt with questions that were very interesting to me; I had also found Augustine himself to be a compelling figure since reading City of God in high school, so it was natural for me to circle back to Augustine when deciding on a dissertation topic.

BCSR: What is the significance of your research?

Benjamins: The primary significance of my research has to do with how we read Augustine and his City of God. The bishop and his famous book have been, to a large extent, the preserve of theologians and philosophers. While their scholarship has successfully unearthed the theological richness and philosophical complexity of Augustine’s thought, there is still work to be done to situate Augustine more concretely in his Roman imperial context, and my dissertation contributes to that project by reassessing Augustine’s relationship to that empire both personally and ideologically.

The prevailing scholarly orthodoxy holds that the Augustine of the 410s drastically relativized and desacralized the historical significance of Rome and its empire, and that the other-worldly, eschatological orientation of his philosophy of history represents an indelible rupture with traditional Roman perspectives. On this reading, Augustine sharply devalues the “earthly city” (in all of its manifestations) in favor of the “heavenly city,” the “city of God,” the community of true believers which will only find its full realization at the end of history. As a corollary, Augustine is taken to redirect attention away from the pursuit of earthly felicity, either on the individual or societal level, toward the attainment of heavenly bliss: in short, away from the saeculum and toward the world to come. I argue instead that Augustine, at a moment of profound social change and contestation, proffers a new ideology of empire, of Romanitas, and of gender—one which, despite its Christian inflection, displays close engagement and significant continuities with earlier Roman literature. By reevaluating Augustine’s central but still understudied work, I integrate him firmly into his time in ways that go beyond the theological.

My research also bears implications for how we think about “Christianization” in late antiquity. Augustine tends to be seen as the hinge between classical antiquity and the Christian Middle Ages, and as such he is often pinpointed as the definitive architect of new and distinctively Christian formulations of “virtue,” “felicity,” and the like, or of a linear philosophy of history. By showing the entanglement of these Augustinian notions with earlier Roman writings and contemporary imperial discourses, I complicate genealogical stories that are reassuringly tidy but too often simplify the complexity of Augustine’s thought and the diverse stock of his intellectual and literary influences.

BCSR: What influence has BCSR had on your research?

Benjamins: BCSR has been an incredible resource not only in refining specific aspects of my research but also in shaping the ways I approach religion in antiquity. Two BCSR faculty members, Susanna Elm and Duncan MacRae, are on my dissertation committee and their mentorship has been an enormous benefit. Susanna’s notion of Christianity as a quintessentially Roman imperial phenomenon has shaped the way I approach texts like Augustine’s City of God, while Duncan has helped me to think more deeply about the limitations and potential pitfalls of “religion” as a heuristic category for antiquity. David Marno and Stefania Pandolfo, who were among the faculty facilitators of the New Directions in Theology seminar, prompted me to wrestle with the connection between language, truth, and metaphor in the context of religious studies. Given the many ways I have benefited from BCSR, I’m excited to be able to share some of my research in a more popular format through BCSR’s Community Outreach Program, with a forthcoming talk on Christianity and slavery in the later Roman empire.

BCSR: How did the New Directions experience influence your work?

Benjamins: The New Directions in Theology cohort was a tremendous asset in the early stages of my dissertation writing. Although most of my scholarly research has been oriented around religious topics, I have had little formal training in the study of religion. For this reason, it was extraordinarily helpful to encounter the work of seminal theorists in the anthropology of religion, like William James, Émile Durkheim, and Clifford Geertz. The faculty facilitators for New Directions did a wonderful job in fostering lively and far-ranging discussions on these and other works. What I appreciated most about New Directions was the opportunity to learn from colleagues who work in very different corners of religious studies and who come from different disciplinary orientations. As we discovered, the highly particularized questions in which each of us was immersed often had a much larger resonance. For instance, Ussama Makdisi’s work on religious sectarianism and co-existence in the Middle East raised questions about “ecumenicity” and secularization that also bear on the religious landscape of the late Roman world. Some of our most memorable conversations focused on questions of discipline and method: how, for instance, the cultural anthropologist relates to her subject differently than the historian, and what are the implications of such differences in posture and orientation. That vibrant intellectual exchange is one of the things I will remember most fondly about my time at Berkeley.

BCSR: What are your future research and career plans?

Benjamins: In the short term, my energy is focused on completing the final chapters of my dissertation, which I will be defending in the spring. At the same time, I’m also working on a few side projects. One is an article on Against Symmachus, a poem written by the Spanish poet Prudentius in the early 390s. I’m especially interested in the first preface of Against Symmachus, where Prudentius retells the story, told in Acts 28, of Paul’s shipwreck on Malta and subsequent deliverance from a snake attack. I argue that Prudentius’ amplified version of this narrative subtly explicates the Acts passage as a commentary on the primal serpent of Genesis 3 and Revelation 20, while also alluding to the serpentine deaths of Laocoon and his sons in Book 2 of Vergil’s Aeneid.

A separate project, growing out of a history thesis I wrote at Hillsdale College, is a monograph on a sixteenth-century controversy over the omnipresence of the glorified Christ in the Eucharist. My manuscript concentrates on a little-studied debate between the Italian Reformer Peter Martyr Vermigli and the German Lutheran Johannes Brenz in 1560-1562. I show how Vermigli’s and Brenz’s theories of presence and place serve to illuminate broader patterns of intellectual appropriation, continuity, and innovation with regard to Christology and the utility of Aristotelian philosophy.

I’m also on the job market this fall. Since my research is located at the intersection of cultural history, classical studies, and religious studies, I’m applying to academic positions in both classics and religious studies (with an emphasis on the history of Christianity). I’m excited to find a home at an institution which values both research and teaching.